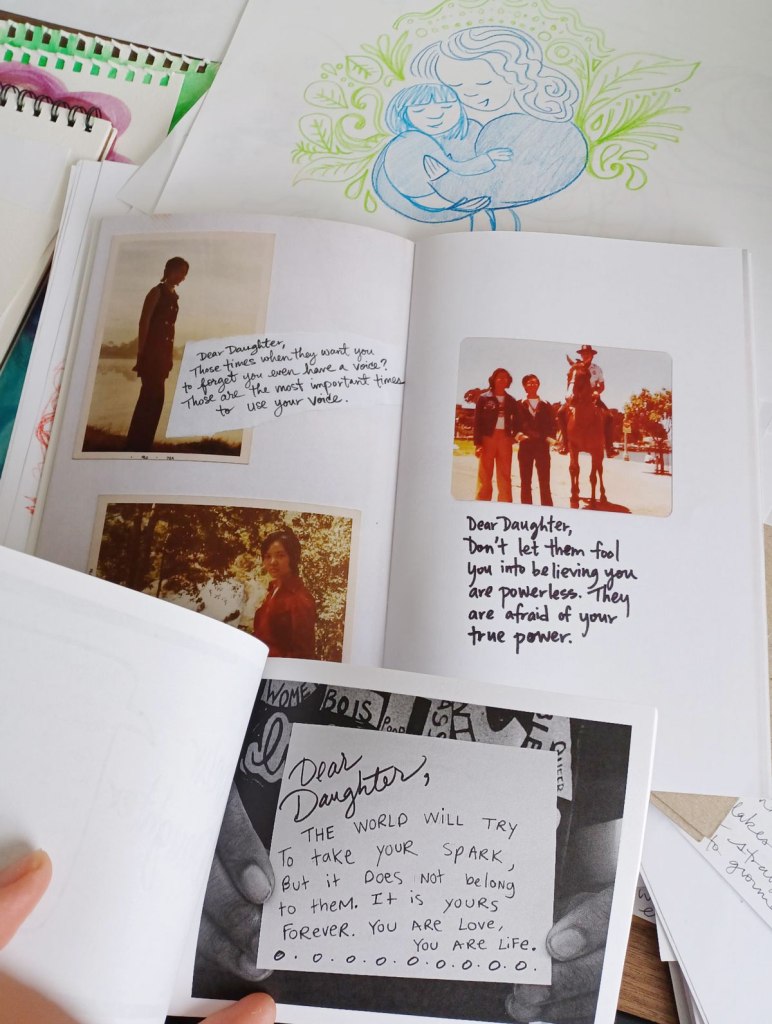

I’ve reprinted the Dear Daughter zine after slowly letting them go out of print back in 2019!

These books, this project, this work, these practices, these ritual experiments resonate with children of immigrants (regardless of race, lest we fall into conflation of BIPOC as identity). They also touch into something around the inquiry and reckoning with the sacrifices and choices that our parents made out of love but which also created seemingly unbridgeable distances, wherein our clumsy attempts at connection keep getting lost in translation.

The Dear Daughter project believes in our ability to understand each other across space-time despite the language barriers (literal, metaphorical, and/or ontological).

Dear Daughter and all the ways it has taught me and all the ways it has grown as a practice over the years remains special to me. It also remains unfinished, as in ongoing. So I am happy to have this iteration back in the rotation.

There was a protective part of me who decided to take this archive off the (literal) table because I wasn’t going to sell out my family history and parents’ photos as commodities for the white gaze.

There are subtle nuances to how different comics shows and zine fests feel in different contexts — sometimes they feel more connective and community oriented, sometimes they feel more commercial and sales oriented. The racial and class demographics of a show’s audience and participation affect this equation via context and patterned ways of being. I’ve started tracking how I feel after a day of tabling as data for deciding which shows I prioritize and participate in year to year.

This often has little to do with how well the books themselves ‘sell’. I treasure the interactions where my work touches something inside of someone, and they are able to be with that connection, and they leave moved (whether the literal zines leave with them or not). There are also a lot of times when my work activates something that someone’s not ready for or weren’t expecting in an afternoon’s shopping trip (zine fests are just crafts fairs, right??) and they also share that — usually to the tune of dropping the zine like a hot potato and running away from the table with a parting “oh this is going to make me cry. (how dare you?)” I’m learning to be okay with that body knowing as well. I respect people’s boundaries as I accept more and more that I can’t control how the work I put out into the work is interpreted — nor even by whom.

Still, we do have some control over how and when and with whom we share. In hindsight, the whiter the contexts, the less comfortable I felt sharing Dear Daughter and all its related forms and offshoots.

I first felt the slight ick during my first time tabling at Portland Zine Symposium in 2017.1 Until that point, I had mostly tabled in the Bay Area, where it didn’t even occur to me that I might need to protect aspects of my work from the warping nature of the white gaze. That I might be reduced to cultural identity, that my culture might be tokenized, that anything or anyone thus packaged might be understood as something sellable, extractable, reproducible, consumable.2

At the time, all I could name was that the show felt a little more commercial to me, that I left feeling a little less connection, and that I regretted selling Dear Daughter zines in that space. It might have been around then that I started questioning whether it was a ‘sell-out’ move to be ‘using’ my parents’ photos and memory in this way. But do you understand that that wasn’t because my motives had changed, but because the context shifted how others were perceiving the work, which in turn affected how I perceived my own work’s intentions? This project has always been a channel for communication and healing, and the offering of the archive as a physical zine has been a way to share it more widely and more tangibly. There are ways in which money can change hands as a form of gift exchange that doesn’t change the nature of the gift, and there are ways in which money can change hands in ways that turns gift into commodity in ways that severs the bond between those hands.3

Eduoard Glissant asserts our “right to opacity” as a right to refuse legibility to those seeking conquest. Alexis Pauline Gumbs reminds us that “the quiet of the hunted is learned” and asks “The quiet of the hunted. Is it sovereign?” She celebrates the “fugitive you cannot find a record for [as] the most successful fugitive of all.” Fred Moten invokes the “full richness of [the blur’s] resistance to valuation”.4

I took Dear Daughter off the table as a protective measure. It was both resistance against reductive legibility AND too-heavy armor against being seen. The line between empowering and disempowering, between opacity and obscurity, is more of an improvised line dance when it comes to visibility and vulnerability and hiding and defensiveness. My relationship with my Dear Daughter zines is just one fractal example of my overall relationship with the whiteness of the Pacific Northwest. It shows me how immediate those assimilative effects were upon moving, and how deeply internalized and embedded the pathways toward self-invisibilization already were, and how naïve I was in underestimating how decimating it would all prove to be to my sense of self and to my creative voice.5

Jennifer S. Cheng asked in a workshop on Bewilderment:

“What doors have you shut in your writing/art-making because of what you’ve been told about legibility, coherency, wholeness, universality? What might it mean to open them and walk through—what is on the other side of the door?”

To circle back to the books, in taking Dear Daughter off the table, I was also excising part of myself as a zinester, and shutting doors to possible connections amidst all the risky waters of modernity and isms. The shame of taking things off the table is that the work might not reach the persons who really need these beacons of “you’re not alone” in environments where majorities pressurize towards assimilation, unwelcome, or erasure. Thus reinforcing (and complicit in) the very whiteness of fests where things like Dear Daughter don’t exist to complicate anything.

The Dear Daughter project is a form of ancestral time travel. It isn’t science fiction, but it reminds us that the (colonial) stories we’ve been told about our aloneness are fictional. The Dear Daughter project remembers us into versions of the world where our ancestors and their wisdom are here and always available to us.

I can’t control how people perceive this work. I don’t need to equate people’s reception of the work to the value of the work or to my own value (or I have learned not to, am in practice of not needing to).6

What I can do is say a prayer of intention or cast a spell of protection over my works and my table display before a show starts. Pray that my books may find good homes, that they may find their way into the hearts of the people who need them. Pray that my work elides the attention and notice of those who would consume me or exoticize us. Pray that they resist and subvert commoditization — that they know they can always sideslip that dehumanizing gaze. That they can “play dead” and seem inert or amateurish or unappealing to those who are not meant to see them, who do not know how to honor their time and effort to be here.

I continue to be grateful. I honor their voice. And my own. And that is enough. Because that is everything.

FOOTNOTES

- Ironically and wonderingly, the zine fest was hosted in a former furniture store space that would eventually become APANO’s Orchards at 82nd.

- Obviously, I don’t attribute this much power or intentionality to the random white lady who stops at my table and says something vaguely vexing or dismissive about my offerings. I only name these things as the indeed-intentional systemic forces that have shaped the grooves by which her and my behaviors play out against and with each other. Also, obviously, shows are usually a mixed bag of these forces — both connective and commoditizing. But if I continue with the obviouslies, then I will be writing to whiteness when I could instead be talking straight to you.

- See Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift for more on the differences between gift and commodity and how commoditizing our interactions severs the bonds of debt that actually weave community. (Hopefully and eventually, I’ll have an essay on this that I can point you to as well.)

- See: Edouard Glissant’s essay “For Opacity”; the Refuse section of Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ Undrowned; Fred Moten’s Black and Blur (h/t for this last one to Christine Imperial).

- …or to cast this not-knowing without judgement, there is a certain kind of innocence that racialized parents grapple with in terms of: how much do you impart the realities of American racism to your children and when. See Aracelis Girmay’s essay “From Woe to Wonder” in the Paris Review. The Asian immigrant flavor of preserving our innocence tastes like swallowing whatever bitterness comes your way with a (in my parents) Confucian acceptance. As if never talking about your pains and aspiring towards class mobility to afford privilege will make life sweeter for your children. In a way it does, but it also shields them from wholeness and integration and ‘radical acceptance of what is’ and true solidarity in other ways. At some point, it becomes denial — and that is yet another razor’s edge, slippery slope, blurry line line dance, et al. Our shared political analysis and ongoing awakenings to the realities of the world thus become vital to being able to show up in honesty and wholeness in our lives.

- This is called boundaries rooted in self-worth, which is a whole nother essay — potentially a book. For now, it is an embodied practice and challenge until it transforms me from the inside out to the point where everything I write won’t be able to help but speak from this space of love.